Bryan Laffitte has had a long career at Novartis in San Diego, California—with some twists and turns. After spending thirteen years at Novartis in a variety of roles, he explored opportunities in venture capital before joining DTx Pharma, a biotech focused on developing siRNA-based therapies for neuroscience indications.

Novartis acquired DTx in 2023, returning Bryan to his roots. This time, he’s leading a unified genetic medicines group as Executive Director in Neuroscience within Biomedical Research. The team brings together the group’s gene therapy and xRNA platform expertise to take on some of the biggest challenges in genetic medicine and accelerate the development of next-generation therapies for neuromuscular and neurodegenerative indications.

We talked to Bryan about the potential ahead:

First, what is "genetic medicine"?

In the Neuroscience group here in San Diego, “genetic medicine” includes both gene therapy and xRNA technology platforms that we’re using to target genetic drivers of disease. These approaches can be used for not only genetically driven neuromuscular diseases, but also to drug difficult targets in more common diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

How did this team come together?

How the group came to be is part of the Novartis San Diego story. The San Diego area has been a real center of excellence for genetic medicine—much of it focused on neuroscience. Novartis acquired Avexis here in 2018 and then DTx in 2023. In 2024 we added Kate Therapeutics, which had multiple programs in the neuromuscular space.

The programs we brought in included gene therapies and oligonucleotide therapeutics, but they were largely targeting the same indications. In many cases they were even using very similar techniques and technologies—similar ways of analyzing gene expression or functional outcomes, for instance. We realized that, instead of having the xRNA group and the gene therapy groups separate in Neuroscience, we could put them together so that the teams could learn from each other and build on each other's expertise.

And I would add that it's not just Neuroscience involved in making genetic medicines here. We also have the Biologics Resource Center (BRC) generating the gene therapies, Global Discovery Chemistry (GDC) generating the xRNAs, and Discovery Sciences colleagues who are innovating on the delivery component—determining which receptors or uptake mechanisms are important. There are these synergies between teams that work very closely together in order to create these great new molecules.

What are some of the big challenges and opportunities in this field?

For many years, one of the biggest challenges for genetic medicines has been delivering them to the appropriate tissues. In the past several years, delivery of oligonucleotides to the liver has largely been solved, and more recently researchers in the field have been able to effectively deliver oligonucleotides to other tissues. For instance, in addition to our work in Neuroscience, Novartis has programs focused on delivery to the heart and specific cells in the kidney as well.

And then with gene therapies, first generation treatments would go to the liver, which can be detrimental and limit delivery to the intended tissues. More recently, companies including ours have developed technologies to improve the delivery of gene therapies to tissues of interest and reduce delivery to the liver. Some second-generation therapies are coming towards the clinic now and look promising, and we anticipate the field will continue to learn and improve.

What are the advantages of using genetic medicines in Neuroscience versus other modalities?

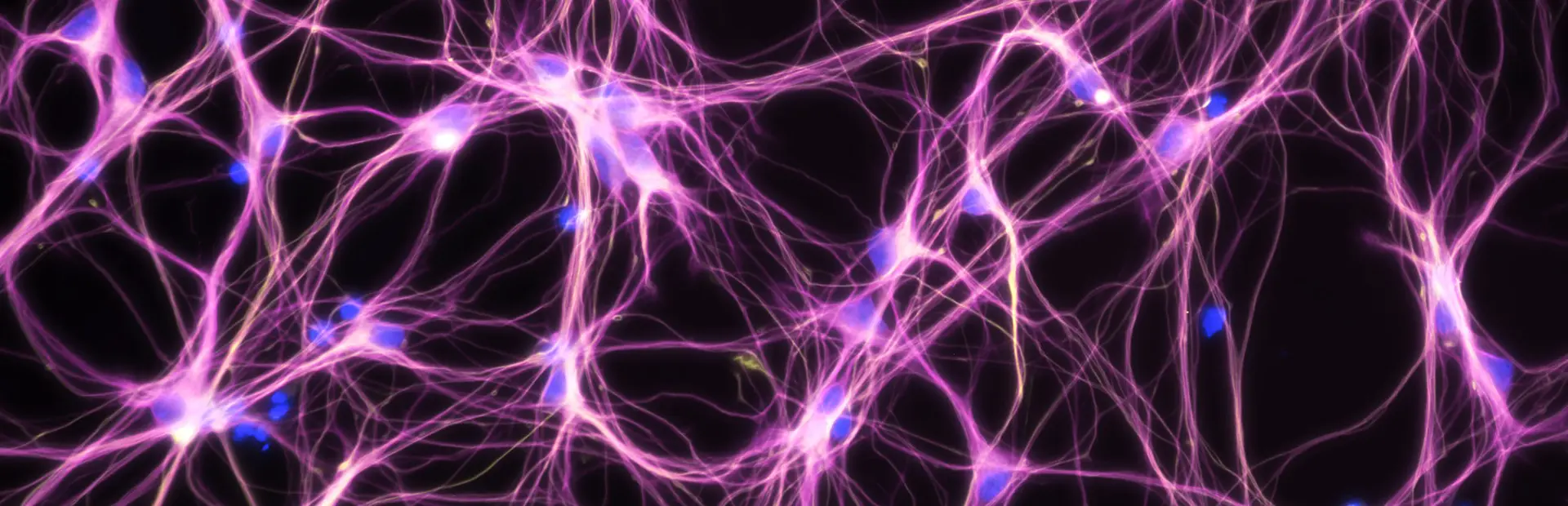

In Neuroscience, our strategy around neuromuscular and neurodegeneration is to address the genetic drivers of disease. There's a great deal of understanding of the genetic causes of these conditions but it turns out that in most cases, those genes are not druggable by the traditional low molecular weight compounds or biologic approaches. Genetic medicines offer a precision approach to going after those targets. For instance, small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a double-stranded oligonucleotide that's complementary to the gene you're trying to target, so you can generate a very highly selective therapy to specifically hit your target that, for the most part, wouldn't hit other genes at all.

Having the ability to get to the appropriate cell types and target genes with high specificity has opened up a lot of these high-quality targets in the neuroscience space—“high-quality” meaning that there is human genetic evidence to support their role in disease and therefore modulating those targets should have a higher likelihood of being successful.

In neuroscience, our strategy around neuromuscular and neurodegeneration is to address the genetic drivers of disease... Genetic medicines offer a precision approach to going after those targets.

What developments should we watch for in this space?

As I mentioned, delivering therapies to treat neuromuscular and neurodegenerative diseases has been a longstanding challenge. We have generated capsids that go to muscle and heart tissue, with a meaningful reduction in the amount going to the liver compared to previous generations. These show potential for genetically driven neuromuscular diseases. We are now working to generate capsids that could potentially deliver gene therapies into the central nervous system (CNS)—looking for ones that could effectively reach the brain and treat neurodegenerative diseases.

And similarly, we are developing technologies for delivery of oligonucleotides into CNS through peripheral dosing—what you might call blood-brain barrier “shuttles.” In general, the blood brain barrier restricts the entry of siRNAs into the CNS. Our team and others are looking to sort of “coopt” natural blood-brain barrier crossing mechanisms; the brain needs essential nutrients—there are transporters for amino acids, glucose and hormones, and transporters for other things that are needed in the CNS—and so we're looking at some of these as potential transport mechanisms to help us effectively get our siRNAs into the CNS for therapeutic purposes.

What do you think the establishment of the new Biomedical Research center in San Diego will mean for your team?

I think the new site will boost collaboration. Currently we have multiple sites in San Diego. Bringing everyone together in one building will generate more natural interaction and there is definitely a synergy to being in the same location—running into the other scientists in the hallways, being able to chat about your projects and spontaneously come up with ideas. And the hub is being designed with collaboration in mind. Teams that have somewhat similar work will have some overlapping work areas and there will be workspaces where teams can temporarily co-locate together to facilitate specific projects—a place to sit together, work closely, and generate ideas rapidly with the goal of bringing results more quickly to patients.

What do you think the future holds for your field?

I’m optimistic that we'll be at the point potentially in the next ten years where we have effective delivery to almost any tissue or cell type we want to target for either gene therapy or siRNA. And I think once the field is at that point, with delivery technologies that are proven and well understood, you'll see the field start expanding out into more novel targets.

Then potentially longer-term after that, I think the capabilities will exist to deliver therapies that can just edit the gene rather than modifying the product downstream. Gene editing is still very early-stage, but at some point it'll become more relevant for neuromuscular diseases and neurodegenerative diseases, and it will depend on the delivery technologies that we're working on now.